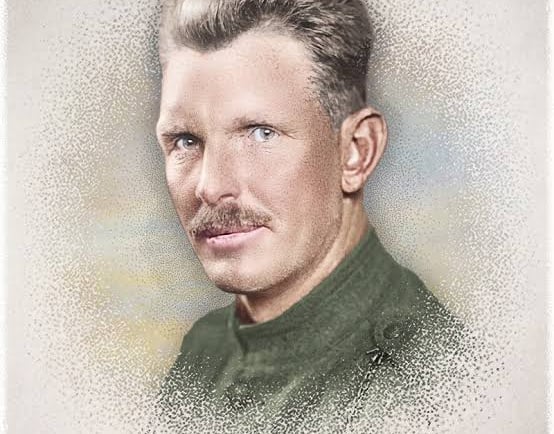

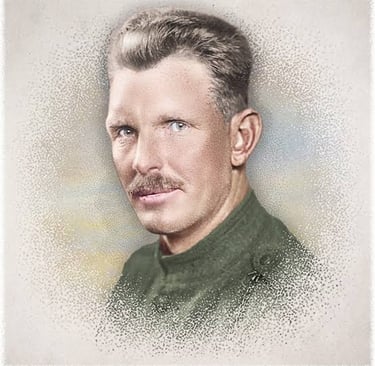

Alvin York's Impossible Solo Victory in the Argonne Forest

HISTORIER

3/13/20253 min read

Alvin York's Impossible Solo Victory in the Argonne Forest

The heavy autumn rain had finally subsided, but fog still hung between the spruce trees in the Argonne Forest on this October morning in 1918. Corporal Alvin York and sixteen other American soldiers from the 82nd Division crept carefully forward through the undergrowth, on a mission to take out German machine gun positions blocking the American advance.

York, a 30-year-old former pacifist and deeply religious man from the Tennessee mountains, had initially applied for conscientious objector status when the United States entered World War I. After deep moral struggles, he had finally decided to serve, but promised himself that he would only kill when absolutely necessary to save lives.

Now, deep behind enemy lines, his conviction was put to its ultimate test.

As the Americans approached a small clearing, all hell broke loose. A shower of machine gun fire tore through the air around them. Six American soldiers, including Sergeant Bernard Early who led the patrol, fell immediately. Three others were wounded.

York and the seven remaining unwounded Americans suddenly found themselves surrounded by over thirty German soldiers who had been working on laying telephone cables, in addition to the machine gun positions on the height above them. The German ground troops charged toward the Americans and took them prisoner, including the wounded Sergeant Early.

But they had overlooked York, who lay partially hidden behind a large tree stump.

What followed is one of the most extraordinary individual combat actions in military history.

When the Germans began leading the American prisoners away, York stood up. With his Springfield M1903 rifle raised, he methodically began shooting down the German soldiers. This was not panicked fire – it was the calm, methodical shooting of a man who had spent his entire life hunting in the Tennessee mountains, where every cartridge had to be counted and every shot had to hit.

York used a hunting technique he had learned in the mountains back home: He shot the rearmost enemies first, so that those in front would not immediately discover where the shots were coming from. With incredible precision, he hit German soldier after German soldier, all with lethal head shots.

"I just couldn't miss," York later recounted. "Every time I pressed the trigger, a German fell. It wasn't me who aimed and shot. Something else, a force far greater than myself, guided my aim."

The machine gun crews on the height swiveled their weapons downward and concentrated fire on York, but the American marksman remained untouched amidst a storm of bullets hitting the ground and trees around him.

When York had emptied his rifle magazine, a group of six German soldiers, led by Lieutenant Paul Vollmer, fixed bayonets and charged toward him – convinced that the American must be reloading.

York, who was on guard against precisely this, drew his Colt M1911 pistol. In a display of shooting skill that seemed impossible, he shot with lightning-fast precision the rearmost German first, then the next rearmost, and continued forward – contrary to normal tactics. This unexpected approach created confusion and panic among the attacking Germans, who had expected him to shoot the foremost first.

All six fell before they could reach him with their bayonets.

Lieutenant Vollmer, having seen enough, shouted "Übergibt euch!" (Surrender!) and blew a whistle to signal surrender. The remaining German soldiers laid down their weapons. York and the surviving Americans took 132 German prisoners – including four officers and several machine gun crews.

When York led his prisoners back to the American lines, the numbers were so incredible that his superior officer, Major George Edward Buxton, initially refused to believe the report. An investigation was launched, which confirmed York's feat. The official report credited him personally with 28 killed German soldiers and 35 neutralized machine gun positions.

His ability to survive the intense crossfire remains a mystery. German investigating personnel who examined the scene later could not explain how a single shooter had avoided being hit from so many angles simultaneously. Some German survivors claimed that York must have had an entire company with him, as they could not believe that one man could shoot so accurately under such intense fire.

For his incredible achievement, York was awarded the Medal of Honor, America's highest military decoration, as well as the French Croix de Guerre. His shooting skills – developed through lifelong hunting in the Appalachian mountains – combined with exceptional calm under extreme pressure, made the impossible possible.

As York himself put it: "When war came to my country, I did my duty as I saw it, but I didn't love it. And I still don't love it. I don't know why, but I just pointed where I saw them, and the Lord repaid tyranny with justice."

Historic Shooters

Explore stories about the most remarkable shooters and their incredible achievements.

Biografier

geir@otimo.no

© 2025. All rights reserved.